books

Unread

Jan 18, 2025

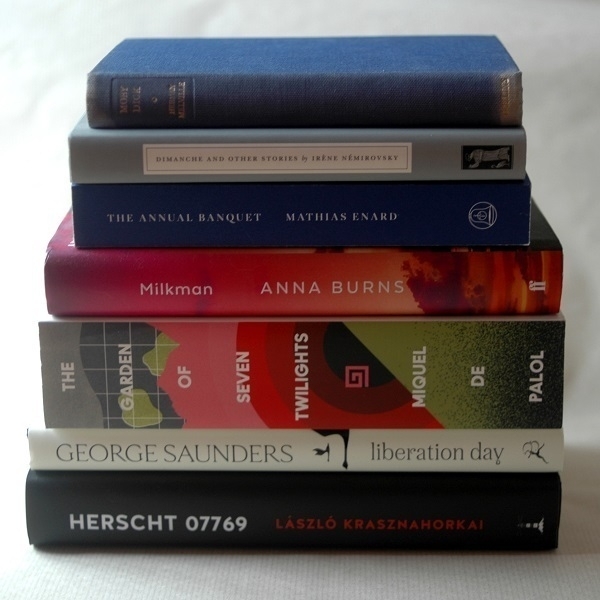

Pictured above is my current TBR pile, comprising seven books, namely (from the top): Moby-Dick by Herman Melville; Dimanche and Other Stories by Irène Némirovsky; The Annual Banquet of the Gravedigger’s Guild by Mathias Énard; Milkman by Anna Burns; The Garden of Seven Twilights by Miquel de Palol; Liberation Day by George Saunders and Herscht 07769 by László Krasznahorkai. The newest arrivals are the two volumes at the bottom. Having much admired Saunders' Lincoln in the Bardo, I thought I’d try one of his short story collections. And I’ve been a fan of Krasznahorkai since the turn of the century, when The Melancholy of Resistance was the only novel of his available in English, so I was quick to buy a copy of Herscht 07769 when it was published a few months ago.

Other titles have been in the pile since 2023. I don’t know why I’m quite so hesitant to get around to Énard’s work. His Street of Thieves rested unread on my shelves for at least two years before I began it. I wasn’t quite as tardy with Compass which only had to wait for six months or so. The title at greatest risk of permanent residency in the pile is The Garden of Seven Twilights. I failed to appreciate when I ordered it quite how hefty a brick of a volume it would be: 880+ pages of smallish print. It daunts me. Of the others, Milkman, and the ’50s copy of Moby-Dick were cheap charity shop purchases; whereas Dimanche was part of an on-line order placed directly with the publisher. I have every intention of reading most of these by the end of this year.

Il Coniglio d'Oro

Oct 25, 2024

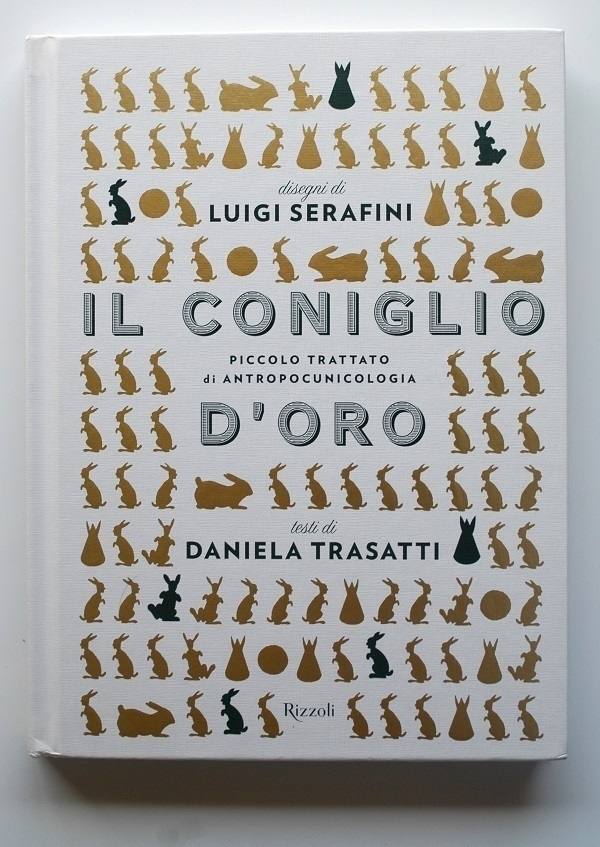

I’ve long been an admirer of the Italian artist Luigi Serafini’s Codex Seraphinianus, so when I first learned, ca. 2015, of another book he’d illustrated called Il Coniglio d’Oro (‘The Golden Rabbit’) I was intrigued. At that time, however, money was short and it didn’t seem like a justifiable purchase. I’d forgotten all about it until a few weeks ago, when a search at Amazon turned it up – still available, and indeed discounted: I ordered a copy.

It’s a curious book, billed as a piccolo trattato di antropocunicologia (‘little anthropolapine treatise’). Serafini’s illustrations are once again a delight: variously bizarre, whimsical, and unsettling. Here are a few details: 1, 2, 3. With Serafini getting top billing on the cover, I wonder if perhaps the illustrations came first and the text was then commissioned to accompany them. Written by Daniela Trasatti, it begins (after a prologue) with some information about the natural history of rabbits and then a broad-brush survey of the appearances made by rabbits in human cultural history. Rabbit-related symbols and traditions are outlined; characters like Peter Rabbit, Bugs Bunny and Miffy are discussed.

Might this be a gift for the Italian-speaking rabbit enthusiast in one’s life? That would depend very much on the nature of their enthusiasm, with the latter parts of the book given over to a survey of the rabbit in culinary history, followed by twenty-one rabbit-based recipes. It’s all at once an art-book, an essay, and a cookbook. Unsure where the volume should go on my shelves I’ve placed it here for the time being.