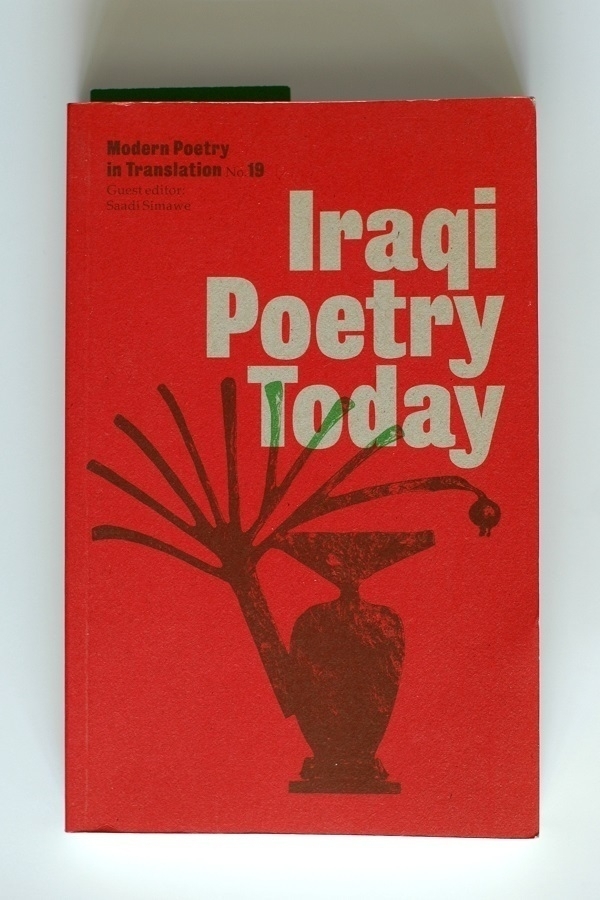

Iraqi Poetry Today

Iraqi Poetry Today is an issue of the periodical Modern Poetry in Translation published in 2003. ‘Today’ in this context was a time when the country had left the frying pan of Saddam Hussein’s regime for the fire of the Iraq War. In his introduction, editor Saadi Simawe laments “the difficulty of finding major sources of Iraqi poetry since 1980, when the series of wars began” and regrets his inability to include many of “the new generation of poets who began writing under sanctions and do not have access to publication”. For these reasons and others, the majority of the poems featured are by exiled authors.

As well as translations from the Arabic, there are a number from the Kurdish and a few from the Hebrew. The Kurdish poems represented are for the most part fairly straightforward expressions of nationalism – understandable given Kurdistan’s status as a nation that isn’t a country. There is a great deal more variety and complexity in the poems from the Arabic. Some of the most appealing works for me were ones incorporating Western influences, bringing them on to something more akin to familiar ground. Fadhil al-Azzawi’s poems, for example, were among my favourites in the book. Elsewhere I hadn’t expected to read a poem referencing T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral and less still another in praise of the Welsh author R.S. Thomas.

In a different vein is the poet given the most space in the book: Muzaffar al-Nawab. A single long poem ‘Bridge of Old Wonders’ takes up thirty-one pages, followed by another four pages of explanatory notes. It’s a work transcribed from a live performance recorded on cassette tape. Its first part bristles (so I gather from the notes) with historical references and allusions to the Koran & to classical Arabic poets. The second half gives powerful rherotical voice to a sense of wounded grievance on behalf of the Palestinians (a recurring note in the very small cross-section of modern Arabic poetry I’ve encountered). The effect for a Western reader who might be considered by al-Nawab as – if not the enemy – at least a part of the problem his complaints and invective address, is as disconcerting as it is impressive.