Paradise Lost

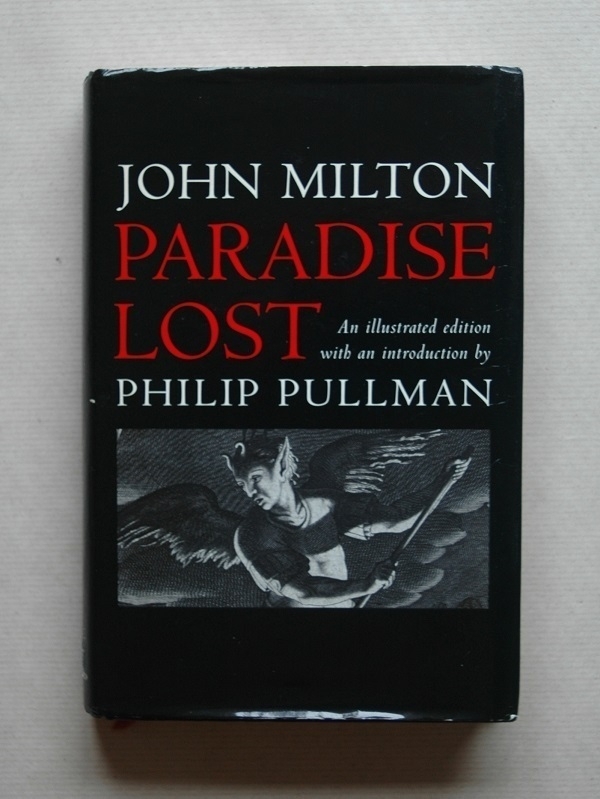

Like many others I was first exposed to John Milton’s Paradise Lost while still at school. I think I would must been fourteen or fifteen when I read the excerpts from Book I of the poem included in one of our textbooks. At infrequent intervals over the intervening decades, I’d be reminded of it by articles praising its virtues, or quoting a few lines from it; and it might occur to try reading the whole thing. Last year, while expanding the poetry section of my bookshelves, I at last bought myself a copy. Looking for a handsome hardback volume I ended up paying £6.49 for an ex-library copy of a 2005 illustrated edition published by the OUP, with an introduction by Philip Pullman.

I was reminded of it again last month on reading a piece about a PhD student teaching the poem to incarcerated students in New Jersey. I pulled it off the shelf during a lull in my working day last Thursday, and had finished it by Sunday. It was more compelling than I’d expected. The Christian mythos has always struck me as unsatisfyingly bizarre, so I was much impressed that Milton had made such a page-turner out of it. It’s not all equally good throughout: the intensity of Books I & II isn’t always maintained; and I thought Book XII at the end, aside from its well-judged closing lines, felt like something of an awkward speed-run through the postdiluvian age.

A continual pleasure was Milton’s sonorous way with an enjambed pentameter, and his pleasingly polysyllabic Latinate vocabulary (with its sprinkling of obscure words like ‘circumfused’ and ‘transpicuous’ – also ‘magnific’, that I’d hitherto encountered in a very different context) which together gave a monumental heft to his ponderous verse. I was surprised by the cosmological passage in Book VIII where, in an account of the creation, geocentric and heliocentric theories of the solar system are entertained, and the possibility of other suns and other planets is hinted at, although at the end of it the Archangel Raphael enjoins Adam to “Think only what concerns thee and thy being / Dream not of other worlds…”

I very much liked the design of the volume, credited to one Bob Elliott: the 17th-century illustrations; the two-colour text; the tasteful typography. I raised an eyebrow at Pullman’s name being printed almost as large as Milton’s on the jacket – such is marketing, I suppose. Pullman contributes a ten-page introduction; a further paragraph prefacing each of the poem’s twelve books; and a brief afterword, all of which conveys a fan’s enthusiasm for the work, while remaining unobtrusive enough. No further notes are provided, but as the afterword points out, there is no shortage of explanatory material out there for the befuddled reader, or the idly curious one.