Photogram

Photograms or lumen prints are photographs achieved without cameras; shadow-pictures made by placing objects upon or in front of photo-sensitive surfaces, and then exposing them to light. The first permanent photograms were made by the pioneers of photography in the early 19th Century: Niépce and his “photoengravings”; Fox Talbot’s “photogenic drawings”, etc.

In the summer of 2010 I tried my hand at making a few. The one above was one of my more successful efforts. I arranged four lilac leaves on a sheet of Fomaspeed Variant paper placed outdoors in bright sunlight, with a square of glass holding the leaves in place (it was breezy). I didn’t record how long the exposure time was - I’m guessing it would have been 45-60 minutes. Afterwards I fixed and washed the paper.

Like the other prints I made in this way the resultant image was fairly low in contrast, so I made some enhancements using Photoshop after scanning it. The print captured some fine detail of the leaves' structure in places, but the condensation trapped under the hot glass blurred other parts of the image.

Straight Razors

Pictured above are my smallest and one of my largest straight razors, both of which still happen to have their original boxes. The length of such blades (with few exceptions) tends to be a consistent three inches or so, with their size instead reckoned as the distance from spine to edge - traditionally expressed in eighths or sixteenths of an inch. The French-made Hamon razor at the top of the picture is a mere 7/16, while The 1000 razor below it, made by Taylor’s in Sheffield is 13/16. Even skinnier and stouter sizes can be found, but are relatively uncommon.

I spotted the Hamon in an antique shop in Abergavenny back in 2014, but didn’t get around to using it for years afterwards. Stamped on one side of the tang is Hamon Fabricant Paris France, while on the reverse are the numbers 42/13 (the significance of which eludes me). It has a so-called near-wedge grind, which is to say the blade has an only very slightly concave cross-section, not so far off flatly triangular: which makes it a little stiff and unyielding to shave with. The scales (i.e. the handle) are made of what I believe to be pressed horn. I suspect it may date back to the turn of the 20th Century.

The other razor was a 2021 eBay purchase. The 1000 is etched into its blade with 👁️ Witness 1000 stamped on the same side of the tang, and Taylor Sheffield England on the other. The blade is full-hollow ground, meaning its profile is markedly concave and very thin towards its edge, lending it a responsive flexibility in use (if also a certain fragility). Its scales appear to be hardened rubber, aka ‘Vulcanite’ or ‘Ebonite’. My guess is that it’s of inter-war manufacture.

Both razors were inexpensive (around £10-£15) but had to be sent off for honing to get their edges shave-ready, thereby practically doubling the cost. Both Hamon and Taylor’s are still current brands now, although neither have made razors for many years. The former shifted their focus to supplies for the fashion trade; while kitchen knives and the like are still sold under the latter name.

After beginning to use a safety razor, searching for information about them on-line led me to forum posts extolling the virtues of straight razors. I was intrigued, if apprehensive, at the prospect of using one: when I found a couple of cheap straights at a local antiques market I thought I’d have a go. Those first attempts were half-hearted, however, and proved unsatisfactory. Only in the second winter of the pandemic did I come back to the cut-throat experience, and throwing more time and money at it provided me with much better results. Now I prefer to shave with a straight whenever time permits.

Dark With Excessive Bright

My latest (modern) classical CD purchases were an excellent new recording, warmly praised by the composer himself, of a piece that means a great deal to me: Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians; and Dark With Excessive Bright, a disc featuring two arrangements of the title piece along with four other works by Missy Mazzoli, which also proved to be very much to my taste.

‘Dark With Excessive Bright’ began life as a concerto for double bass and string orchestra. Having a particular fondess of the dark sonorities of the contrabass, I would have loved to hear that on CD, but instead the album is bookended with versions re-arranged so that Peter Herresthal’s violin is the solo instrument. He’s backed by a string orchestra on the first track, then has the sparser support of a string quartet on the final one. The scaffolding of the piece proves flexible enough that both versions work admirably well. The intervening works are a varied bunch all likewise well worth hearing.

I’d been more ambivalent about my previous pair of classical buys: two sets of string quartet recordings featuring music by Philip Glass & György Ligeti.

Issued last year were Quatuor Tana’s première recordings of Glass’s 8th & 9th quartets, the latter adapted from music composed to accompany a stage performance of King Lear. This theatrical 9th is sombre, as befits the play it soundtracked, and features no few sonically striking passages, particularly the section near the close of the restless first movement where the cello takes centre stage; but for all that it seemed to me slightly short on cohesion, and with a finalé that didn’t quite convince; whereas the subtler 8th holds together more persuasively, its melancholy slow movement the highlight.

Ligeti’s two numbered quartets are formidably challenging and played with commanding aplomb by Quatuor Diotima on their recent album Metamorphosis. For all their wit & wealth of invention, though, these are still works I find it difficult to love. When it comes ’50s & ’60s modernist quartets my preference would be for Penderecki’s over these. Also on the same disc is a fascinating two-movement ‘Andante and Allegretto’ by the Hungarian, a relic of the first phase of his compositional career in Budapest when he was obliged to try (at least some of the time) to please the Communist musical establishment.

Blonde Roast

I don’t know that I’ve ever tried the coffee at Starbucks. I do remember visiting at least one of their outlets during my tea-only years, but what I might have ordered there escapes my recollection. I can say, at least, that I’ve lately sampled their espresso coffee beans, such as are stocked at the local Sainsbury’s. I had mixed feelings about the taste of the regular Starbucks® Espresso Roast, which, for me, seemed overcooked (though there were days when I appreciated its brusque robustness). Such charm as it had, however, was counteracted by its tendency to induce headache within half an hour of consumption.

I’m having better success with their Starbucks Blonde® Espresso Roast, which I find very good. Despite being maybe just a tad the other side of my ideal kind of medium-roasted, it has a full yet soft-edged flavour that hits very near the spot. There’s an ample kick of caffeine, and it doesn’t give me headaches. I’d rate it as perhaps my fourth favourite bag of beans since re-commencing my coffee habit. It certainly suits my unsophisticated palate better than the costly Union Revelation Signature Espresso blend I’d been struggling with immediately beforehand.

The Italian-made coffee-cups I started the year with didn’t last the course, with chips of glaze detaching from the underlying earthenware after only a couple of months of use. Pictured above is one of four old Habitat Nil porcelain demi-tasses I’ve been using more recently. They had formed part of a £5 charity-shop purchase. Sadly, they aren’t lasting the course too well either: after some careless breakages, only two remain. I’m still enjoying using my Bialetti Moka Express, despite the lack of crema in the coffee it produces (as illustrated in the image above).

Return Thanks

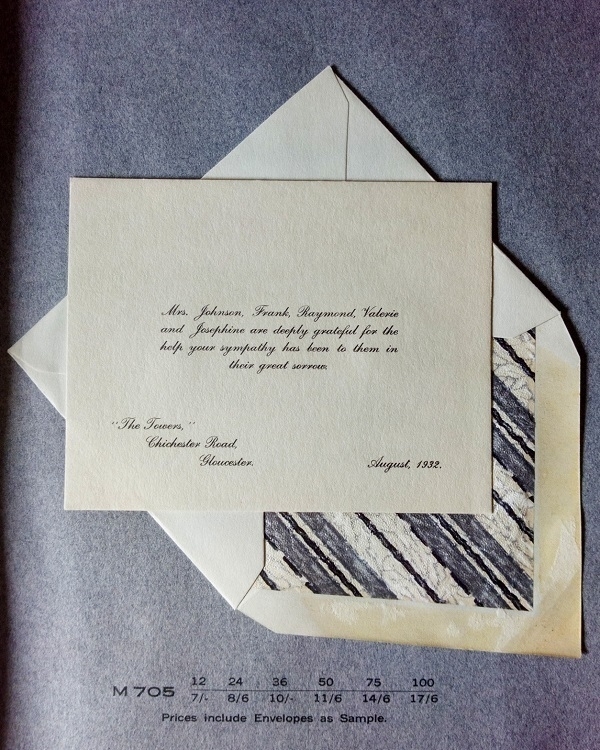

It’s 1932, and Mr. Johnson has died suddenly in Gloucester. His grieving widow and four children have received many dozens of letters of sympathy and numerous floral tributes in the wake of his decease, for each of which etiquette demands a timely note of thanks in reply. Mrs. J. just doesn’t have it in her to tackle this onerous task - but, thankfully, there are services which will supply pre-printed responses in bulk, thereby enabling the family to adhere to the letter of the law of etiquette, if not quite its exacting spirit.

Recently I obtained (via ebay) a sample-book of such pre-printed messages including the example above. On the cover is the text Sharpe’s “Classic” / Return Thanks Stationery / British Manufacture, where Sharpe’s were the manufacturers providing the paper, cards and envelopes; and ‘Return Thanks’ (I presume) their service run in co-operation with participating printers, to supply the requisite personalisation. Loosely held in the book was some documentation relating to The Manor Press Ltd., Colchester, apparently the printers who had owned and used the book. Similar sample books would doubtless have been available for weddings, etc.

A range of paper styles & tints were on offer: hand-made off-white paper with deckle edges; white cards with Victorian-style black borders, or else un-bordered or edged with silver or grey; and also paper in a pale lavender shade, which I thought an odd choice until I learned that lavender/mauve was once recognised as a secondary colour associated with mourning. Some of the envelopes have surprisingly gaudy linings, as in the one above.

The forms of words in the samples are generic: customers may have fallen back on such standard phrasing or would have had the option to supply their own text. In a couple of cases the samples explicitly state that the bereaved “find it impossible to answer letters personally”, by way of explanation for the impersonality of a ready-made reply. In terms of the lettering used, script faces predominate, with sans serif and ‘Old English’ styles the other main options.

Rhys Davies

The books in the photograph above contain most of the collected short stories of the Welsh writer Rhys Davies (1901–1978). Some others were, early in his career, published singly in limited editions: I have a few of those too. Possibly there were more besides which only ever appeared in periodicals, and which remain uncollected. Not shown are the Selected Stories of 1945, the Collected Stories of 1955, nor any of the posthumously-published editions of his tales. He is reckoned to have turned out about a hundred short stories and twenty or so novels over the forty-odd years of his writing life.

That life began, the story goes, after he’d left Wales for London and had found work in a suburban clothing store. One weekend he happened to pick up a copy of a literary quarterly called The New Coterie at a bookshop, and, reading the stories within, felt he could write just as well. Putting pen to paper on a wet Sunday afternoon, his first three tales “seemed to pour out like the rain”. These first attempts were accepted for inclusion in the next New Coterie, and, together with a few others, were published in 1927 in a slim paperback volume The Song of Songs. The same year saw the appearance of Davies' debut novel, The Withered Root.

Eight further full-scale story collections followed. My own favourites among them are Love Provoked (1933), the volume where I feel he first exhibited full mastery of the form; and A Finger in Every Pie (1942), the first of his collections I read, and a book I enjoyed so much it got me started on seeking out all the others. Not that I dislike the rest by any means: A Pig in a Poke (1931) may have some rough edges, but also a great deal of charm; and if The Darling of Her Heart (1958) plays it safe at times with some soft-focus nostalgia, there are more forceful moments too. A contemporary praised Davies as ‘The Welsh Chekhov’, which I feel is overstating his case: he couldn’t match the Russian’s depth; but I nevertheless prefer my compatriot’s writing over that of Anton Pavlovich. I’ve had less success with Davies' novels but have only read a few of those to date.

Described by one profiler as “a small, neat, darkish man with a bird-like face and quick eyes”, he hailed from the South Wales Valleys, then a major coal-mining centre. Despite leaving for London as a young man, Welsh settings predominated in his fiction for decades thereafter: whether in realistically-drawn tales of miners and their families from his industrialised home turf; or in stories set in a more or less idealised vision of rural West Wales. Some of the best entertainment in his fiction comes from his vividly-drawn (and frequently headstrong) female characters, from the downtrodden Mrs. Rees in ‘Nightgown’ and her dogged determination to bring one feminine comfort into her harsh life; to the witchy Sian Shurlock in ‘Over at Rainbow Bottom’, suspiciously-often a widow.

Davies was gay - albeit determinedly closeted - with (reputedly) a particular fondness for military men. There are hints as to his orientation here & there throughout his books, but only very seldom did he approach the subject of homosexuality more directly, such as in the stories ‘Doris in Gomorrah’, ‘Queen of the Côte D’Azur’ and ‘Wigs, Costumes, Masks’. Interestingly, none of these three appear in the 1955 Collected Stories, which gathered together about half of his stories written up to that point. In his brief Preface for the book, he wrote that the pieces included “yield me various degrees of satisfaction” while those omitted “cause me various degrees of unease” - an unease that may in some instances have had an extraliterary dimension.

Robot/Alien

I’ve a soft spot for this photo of a piece of grafitti seen on a wall somewhere in the Manor Farm estate, north Bristol, in the summer of 2013. I took it with a Mamiya C330s Professional TLR camera, fitted with its standard 80mm lens-pair, and loaded with Fuji Provia 100 slide film. It was the one striking frame out of an otherwise lacklustre dozen on the roll, with the remainder split between depictions of a deserted playground, and mediocre shots of my dog.

It’s an unsophisticated artwork, but I love the depth of the red background and its contrast with the blue of the figure, whatever it might be: robot? alien? other? I love that the texture of the underlying concrete shows through. And I love how the artist succeeded in giving the robot/alien such an ambiguous expression. Is it a happy smile? A grimace of fear or anxiety? For me, the paint drips in the whites of its eyes are suggestive of something other than straightforward good cheer, but then what do I know of alien/robot ways?

Screwpull

I admit to feeling a sentimental attachment to certain objects. This oftenest happens with useful items I’ve owned for a long time. A case in point is the somewhat distressed-looking ‘Screwpull’ corkscrew shown above, of which I am very fond. I’ve had it for twenty-three years, and it has opened many hundreds of bottles of wine. Only on a handful of occasions has it failed me (and then only due to operator error, or a bad cork). Every other time it has been a joy to use.

Along with the joy, other feelings can sometimes be disturbed when I pick it up, like the lees in the sort of fine wines I can’t afford. It was a wedding gift from an old friend - but now I’ve been a widower for a decade, and the friend and I have long since fallen out of touch. Such things provoke reflection. I won’t be needing a corkscrew for the screw-cap bottle of New Zealand Pinot Noir that’s next to be opened. In line after that, though, is a nice-looking bottle of Barbera d’Asti, which will need uncorking. When I open it I’ll raise a glass for my late wife, and for Dr. M., whose excellent gift the corkscrew was.

In-Car Entertainment

The car I had before the car I had before the car I have now must have been one of the very last to be made with a built-in cassette-player. This was less than ideal as I had given away or sold all my cassettes in 1998. Its successor had a CD player, which suited me very well indeed. My current car, however, latterly-acquired, is of recent enough manufacture to have no on-board device for playing physical media. It has a bluetooth option if one wants to play music from one’s telephone (I do not). And it has a passive USB connection and a good old-fashioned line-in socket. Plus there’s a radio offering DAB and FM/AM reception.

For me, this new-fangled state of affairs feels like a backward step. Given my reluctance to use a phone for music, an iPod-esque device seems like it might be the best option. I don’t currently own one, but as I ponder what might work best for my needs, I’ve been using as a stopgap a contraption intended for a slightly different purpose: a Tascam DR-05X Linear PCM Recorder. As well as recording, it can play back mp3 and wav files perfectly well (though without any fancy playlist or shuffle options), and it’s equipped with a headphone/line-out socket. I bought it last year intending to use it for recording music from vinyl (which I still have yet to do).

Between ten and twenty years ago I maintained a music library comprising mostly mp3s and flacs, some of which were ripped from my own CDs, and some obtained via other means. More recently I have left that collection gather digital dust, so the tracks available for loading on to the Tascam reflect an outdated picture of my musical tastes. While it has been a pleasure to re-acquaint myself with songs I’ve not heard for years (for example) I’ll need to fire up EAC and get ripping the CDs I’ve acquired over the past decade to get my motoring playlist up to date.

Absolute Black

Having lost my indiscriminate childhood appetite for chocolate I ate relatively little of the stuff until, in my late thirties, I acquired a taste for good-quality dark chocolate. For some time I was happy enough with bars containing 70% or 80% cocoa, then gruadually began to seek out even more intense and bitter confections.

At length I made it to 100%, thanks to Montezuma’s Absolute Black. This has become my chocolate of choice: a couple of small squares of it serve as an excellent pick-me-up on a workday afternoon. It’s not readily available in nearby supermarkets so I’m obliged to order on-line or to stock up on my infrequent visits to Waitrose.

For a change at the weekend I’ll typically switch to something a little more laid-back such as the J. D. Gross Madagascar 70% chocolate from Lidl, or the Peru 85% bars from Co-op.

20th Century LOLcat

Found pressed between the pages of an old book was the newspaper clipping above, depicting a kitten seemingly in a transport of bliss. The caption reads: “Charmed! A kitten over which music has a strange fascination.” I’ve lightly photoshopped the original scan of the clipping, which is rather faded and yellowed.

The book is considerably older than the clipping: a copy of the 1853 eleventh edition of Isaac D’Israeli’s Curiosities of Literature. This is a work I’ve long enjoyed dipping into; I’ve owned several copies of its various editions over the years. At one time I went as far as scanning and uploading a copy of it (beginning not long before Google Books' mass-digitization made it an even more quixotic endeavour than it might otherwise have been). A few years ago I’d been in need of freeing up some bookshelf-space, and deaccessioned a couple of multi-volume copies of the Curiosities, obtaining this single-volume one in their stead.

The specific copy I bought had ostensibly once belonged to the library of the politician Denis Healey, and indeed there’s a pencil inscription inside: Denis Healey / Withyham / May ‘77, at which time he was Chancellor of the Exchequer. I paid £20 for it. I have no way of knowing at what point in the book’s life the clipping was inserted, but like to think that Healey may have placed it there himself.

Wookey Hole Note

Wookey Hole, thankfully, has nothing to do with the Star Wars™ universe. For anyone unfamiliar, it’s a village on the southern edge of the Mendip Hills in Somerset, south-west England; the village named after a nearby limestone cave system. For centuries the area was a centre of paper-making, with the Wookey Hole mill itself, owned & operated by W.S. Hodgkinson & Co., being known for its high-quality hand-made papers.

The Hodgkinson company sold the mill ca. 1951, with paper still manufactured there commercially until 1972. Since then, the mill has been repurposed as a tourist attraction, with paper now only made at the site on a very small scale as an “experience exhibit”.

I imagine then that the box of paper and envelopes above, acquired via ebay, must be at least seventy-two years old. I like that the box informs the buyer of its being “suitable for either steel or fountain pens”: though in my view, as with most hand-made papers, it doesn’t have the ideal surface for either, with the quality of the writing experience very much depending on the properties of the ink one uses. It is excellent paper for typing on, however.

In Other Languages

I’m a monoglot Anglophone yet own several books printed in other languages. Most of these are art-books of one kind or another where the pictures are part of the point, and where proper names, places and dates in the text can furnish some idea of what is being discussed. A certain something, then, is still being communicated across the language barrier. Beyond that, I like seeing how other languages fall on the page: the shapes of their paragraphs; the lengths of their words; the spatter-patterns of their diacritics & punctuation.

For example there’s an edition of Wentzel Jamnitzer’s Perspective corporum regularium (Ediciones Siruela, Madrid, 1993), a 16th-century work presented in facsimile with its original Latin and black-letter German text translated into modern Spanish. Other examples include an exhibition catalogue Mélancolie: génie et folie en Occident (Gallimard, Paris, 2005) and a monograph Bernini Architetto (Electa Editrice, Milan, 3rd ed.: 1996) which are respectively, as one would expect, in French and Italian.

Other volumes allow more or less English to intrude. Margareta Gynning’s study Det Ambivalenta Perspektivet (Albert Bonniers Förlag, Stockholm, 1999) of the painters Eva Bonnier and Hanna Hirsch-Pauli includes a seven-page English summary - more or less an abstract - after the main body of Swedish text. Opus Magnum: Kniha o sakrální geometrii, alchymii, magii, astrologii,…, on the other hand, by Vladislav Zadrobílek et al (Trigon, Prague, 1997) has a virtually complete small-print English translation of its constituent Czech chapters shoehorned into the back of the book.

In a different category are those books whose publishers have striven to be multilingual throughout. Examples on my shelves are Vrubel by S. Kaplanova (Auora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1975) which is in English, French, German & Russian; and Giovanni Lista’s Balla (Edizioni Galleria Fonte D’Abisso, Modena, 1982) in Italian, French, English and German. In the latter case the English translation leaves a good deal to be desired, so I wonder about the quality of the others.

These last are akin to parallel texts (which, in my library, are almost all collections of poetry), where text in the source language is printed on the left of a double-page spread, with a facing English translation. In that vein I have poems given variously in Basque, Catalan, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, Welsh (and perhaps a couple of others I’ve overlooked).

SM5

On the tabletop in the picture above is an Olympia SM5 typewriter resting on a thick felt pad intended to slightly deaden the noise and vibration it produces. Also identifiable (moving clockwise around the typewriter), are a roll of tape; a fountain pen; a couple of letters in need of reply; a sheet of Air Mail / Par Avion stickers; the base of a lamp; a notebook lying on top of something else (loose paper, perhaps); two bottles of Rohrer & Klingner fountain pen ink with a roll of kraft paper behind them; a box of envelopes and some special-issue postage stamps; a dip-pen; a single folded napkin; another fountain pen and a pair of scissors.

The table is ostensibly a dining table but is seldom used for eating and most often employed instead for writing, hence the profusion of stationery.

It was an SM5 that got me properly started with typewriters. I’d first owned an ugly early ’60s Underwood that I’d fought a losing struggle to keep working, but the Olympia, acquired at a junkshop in 2015 - for all of £17 - was a real a joy to use. Within a few more years I’d accumulated a small typewriter collection. Not long after I’d given that SM5 away to a relative, I bought another (the one in the picture), this time from ebay. It doesn’t look as good in colour as in monochrome, which disguises its blotchy nicotine patina and the spots of paint-loss: for all that, the machine still works like a charm.

Astrud

When I bought the instalment in the Compact Jazz series of compilations devoted to Astrud Gilberto, it stuck out of the rest of my music collection at an awkward angle. This was in 1989, when most of my cassettes featured rock, pop & indie music: tantamount in those days to a declaration of allegiance to a particular musical tribe. Gilberto’s easy & mellow jazz-tinged confections were clearly the property of some rival clan, but I knew I loved ‘The Girl from Ipanema’ & wanted to hear more like it.

Thankfully such ridiculous demarcations are much less in evidence nowadays, and one can listen to a little of everything without feeling the need to take sides in some broader conflict. It’s turned out that, unlike the larger part of what I was listening to in ‘89, I still love Astrud’s singing now. I was delighted then to find a copy of her debut solo album in Monmouth the other weekend at ‘The Vinyl Spinner’ market stall. It’s from a budget re-issue series seemingly made for the Dutch market, but there’s nothing wrong with the record within, which carries the familar Verve label, and which sounds wonderful.

It’s very nearly a case of “Astrud Gilberto Sings the Antônio Carlos Jobim Song Book”, with all but one of the tracks (and that the weakest of them) compositions of his. It’s all the better a record for it: ‘The Girl from Ipanema’ and ‘Corcovado’ (the tracks on Getz/Gilberto that first introduced Astrud’s voice to the world) had been Jobim’s handiwork too. Moreover, the composer was also present in person, playing guitar throughout and adding vocals to ‘Agua de Beber’. None of which takes away from Gilberto’s own contribution: her voice brings with it just the right blend of naïve sentimentality and cool melancholy, complementing the songwriting and the arrangements perfectly.

Black Olive Paté

Amidst the sporadic arrivals of nationally-themed groceries one can sometimes find at Lidl, an item I look for (should I happen to see any ‘Italiamo’-branded stock) is this black olive paté, or Black Olive Patè as the label on the front of the jar has it, deploying a grave accent where an acute one should surely be. While in itself it may not quite qualify as a tapenade, it could readily form the basis for one. In practice, though, I tend to enjoy it as it comes, using it as a spread or a dip.

Crane's

I haven’t succeeded thus far in obtaining any of the wares of the notable US stationery manufacturers, which don’t seem to have been sold in any significant quanitites in the UK: it probably just wasn’t economically worth their while to export it transatlantically. I have, however, admired some of the advertising I’ve found on-line produced by the likes of the Eaton, Crane & Pike Company.

Above is a prime example from 1925 featuring a lady with a practically tubular silhouette admiring the box of Crane’s Cordilinear she received as a gift: “in writing paper, the very finest obtainable can be bought for as little as five dollars”, the copy maintains. The following 1924 ad, meanwhile, tries to persuade its readers there would be ghastly social repercussions if they were to use poor-quality stationery. Much as I admire a really nice sheet of paper, the appeal to snobbery here is enough to drive anyone to scribble on something cheap & nasty instead.

Shelf Portrait (Number Four)

Most of my books are kept in my upstairs study/office which, of my few visitors, fewer still will see. There is one small bookcase in my lounge/dining room downstairs: for years I used it for cookbooks and a changing assortment of non-bibliomorphic items. Last year, however, I thought I’d make a semi-decorative feature of it by filling it with a selection of interesting-looking volumes (interesting to me, at least). The current contents of its top two levels can be seen above.

Its shelves have ended up in an odd configuration where two of them are rather close together, permitting space between them only for books no more than about 175mm / 6⅞" tall. As of last summer I had enough sufficiently diminutive volumes to fill only half of it, and there followed an exercise of gathering a variety of compact, presentable-looking books to fill the other half. The top shelf supports a selection of (mostly) non-fiction titles. The most recent addition to it is In Miniature: How Small Things Illuminate the World by Simon Garfield, which I picked up from Stephen’s Bookshop in Monmouth on Saturday and then read that same day.

TLR

Seeing Rolleiflex cameras used in movies made it look like TLR photography would be great fun - Fred Astaire photographing Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face, for example. When I properly took to using film in 2008, I wondered if might try it for myself. Not quite willing to invest in a Rollei, I nevertheless very much wanted a camera with a crank to advance the film, so looked instead at the various Japanese-made TLRs, and settled for a late-’50s Yashica Mat. This I obtained via ebay from a lady whose partner had apparently used it when illustrating the motorcycle repair manuals he wrote in the ’60s.

My Mat is shown above, dressed up somewhat with a lens hood, and with a corrective optic of some sort (intended to help with taking close-up shots, as I recall) placed in front of the upper lens (which otherwise would be less protuberant). I used the camera a good deal for about a year, and it was exactly as much fun as it thought it would be: I always loved using the crank. Then, however, the shutter started to stick sometimes at slower speeds. Learning that there was a repairman still active who had worked in the Yashica factory, I sent it off to him for a CLA: quite a costly exercise with the transatlantic shipping factored in. It worked very well again after that, but only for another three or four years, whereupon the shutter began sticking anew. Subsequently the camera was relegated to a drawer, one from which it has yet to re-emerge.

Sadly, I think my TLR days are now behind me. I shoot film so seldom these days that using a single SLR seems quite sufficient. Plus the costs of film and processing seem higher than ever. Still, I’ll miss the thrill of looking down on to the focussing screen and seeing a bright image on it (such as the slightly out-of-focus one below), and of clicking the shutter and turning that crank.

Soap and Brush

For a proper traditional shaving experience one needs a razor, a brush and some soap. Having tried out seven or eight different brushes over the last dozen years, for the last while I’ve settled on two that I alternate between. The one shown above is a Portuguese-made Semogue 1250 bristle brush with a wooden handle. It cost me less than a tenner and I’ve been using it for two and a half years. The other is an Omega 108 Professional brush (bristle again, but made in Italy) with a slightly larger knot and a plain dark blue plastic handle. It cost the same as the Semogue and I’ve been using it for twice as long.

Also made in Italy is my current choice of soap: Cella, specifically their regular ‘Extra Extra Purissima’ variety in the red plastic container, with its simple but eminently agreeable sweet almond aroma. I stockpiled three tubs of it when Connaught Shaving (also my source for the brushes) had it on offer the October before last (for less than £4 per unit, delivery included). Each tub lasts me several months and I’m still working my way through the second of the three. One of the good things about Cella is its easy-going nature, with even a somewhat underworked lather providing plenty of slickness for a first-rate shave with a straight razor.

Roberta

Last August or so I saw or heard someone singing the praises of Roberta Flack’s debut album First Take (1969). As luck would have it I found a cheap vinyl copy in September; but as luck wouldn’t have it, the disc was in barely playable condition. Still, I heard enough to know I too would be singing its praises in due course.

When I hastened to obtain another copy from a Discogs seller, even at four times the price I’d paid for the first one there was no qualm of buyer’s remorse. I particularly love the opening two tracks, the uptempo opener ‘Compared to What’ and the impassioned ‘Angelitos Negros’. Elsewhere, Flack’s famous version of ‘The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face’ is all the more lovely in the context of the album, and follows a stately cover of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye’, then still a relatively new song.

My luck came good again a few weeks later when I turned up her fourth solo album Killing Me Softly (1973), again on vinyl and again for only a few pounds (albeit this time in better shape). I was well-acquainted with the powerful title track but didn’t know the album included another Leonard Cohen number in the shape of Flack’s version of ‘Suzanne’. Overall I thought the LP almost as good as her first. I had to wait several more months before chancing on album no. 2, Chapter Two (1970), which cost me roughly twice as much as Killing Me Softly, half as much as my second First Take. It gets off to another strong start with Reverend Lee but has a couple of weaker tracks too, such as her less than fully convincing attempt on Dylan’s ‘Just Like a Woman’.

Most recently of all - the weekend before last, returning to my usual haunts paid dividends yet again when I found a copy of her 1972 duet album Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway. This one I’m still getting to know - at first acquaintance I feel it may be straddling the line between the agreeably and the overly smooth: repeated listening will be the test of that. Now I suppose I’m on the lookout for solo LP no. 3, Quiet Fire (1971).

Havana Club

Last night, while listening to Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Jerome Kern Song Book, I reached the bottom of the bottle of Havana Club Selección de Maestros rum I’d been savouring, snit by occasional snit, since last October. It was delicious.

When it comes to spirtuous liquors, my preference has always been for booze (be it whisky, rum or brandy), that has spent a good long while resting in a barrel. I first formed a taste for rums of that ilk between 15-20 years ago, with the Havana Club Anejo 7 Años becoming a firm favourite that consistently offered what was, for me, a particularly appealing quality-to-price ratio. I had better rums; I had cheaper rums; but none that struck me as better and cheaper.

I was tempted last year to try something from the same producer at a higher price-point, hence the now-empty bottle above. It cost about twice as much as the Anejo 7 Años, and, while it afforded fine pleasure, and I’m delighted to have tried it, the extra expense didn’t provide enough extra benefit (for my palate) to justify a repeat purchase.

Menus

One of my less successful typewriter purchases was a 1956 Voss S24 I ordered from a French ebay seller in 2019. It was a good-looking machine that just about worked - albeit never altogether satisfactorily. It arrived screwed down inside its travel case: when I unscrewed it I found two slips of paper that had been stuck underneath on which (so it appeared) menus had been handwritten in pencil, perhaps ready to be typed up. Fortunately the writing is fairly legible, and I’ve been able to at least make a guess at what it all says:

- Potage du jour ou S[alade] de concombre

- Steak. Pommes frites

- Potage . Terrines[?] Crudités

- Rognons S[auce] Madère

- Tarte aux foies de volailles

- quenelles S[auce] Nantua

- cote de porc p. purée

- canard Roti Petits Pois

- Faux Filet Béarnaise

Makes me feel a bit peckish. Printed on the reverse of the same slip, meanwhile, is Cafés BALZAC / Le Régal des Connaisseurs, which could be the establishments where these dishes were served up. The other ‘menu’ (below) includes similar fare, with the following not included on the first slip:

- Petits Salés aux lentilles

- Tête de Veau Vinaigrette

- Escalope Viennoise

Laroche-Joubert

The stationery set shown above is one of a couple I’ve owned that were produced by the French company Laroche-Joubert. This Barbarella set doesn’t have any obvious connection with the comic book or the movie featuring that character: perhaps there was merely an intention to cash in on that phenomenon by indirect association. As might just be visible, there’s a faint image of a woman’s head and shoulders on each page, with the same picture more clearly visible on the front cover of the folder.

The other set (whose product name is Anabelle) likewise has a background image on each sheet (see below), this time a drawing of a figure reminiscent of some of Leon Bakst’s designs for the Ballets Russes. Here, however, the folder’s cover image bears no relation to the one within. I wonder if this one might date from the early-to-mid ’80s, whereas the other one has more of a ’70s look about it - but those are altogether uninformed guesses.

The industrialist and politican Jean-Edmond Laroche-Joubert (1820-84) inherited a paper-making concern from his father, building it into a much larger enterprise, chiefly associated with the town of Angoulême. “The company was known for high quality writing papers that could be watermarked with all sorts of drawings at the choice of the buyer” says his wikipedia page, which ties in with the sets I’ve acquired, in which the paper quality is indeed admirably good.

Orlam

Although more a standoffish admirer of P.J. Harvey’s music than an outright fan, I was nevertheless intrigued on reading a description of her book Orlam (when it was published last year) as “a novel-in-verse written in dense Dorset vernacular”: not the sort of work one might typically expect from a rockstar-turned-author. When I picked up a copy from a bookshop shelf last month I liked what I saw of the verse therein. At the next opportunity I bought the book, going on to read it cover to cover by the end of that same day.

It didn’t strike me as much like a novel, nor would I categorize it as a single long narrative poem: rather it seemed to me “a series of lyrical vignettes” in which the outline of a larger narrative could be discerned. Like a song-cycle where the reader is called upon to supply much of the music, it’s something akin to a concept album in book form. To say it presents an unsentimental look at rural life is putting it very mildly: in no way is it a pastoral idyll. There are moments of quiet beauty, but the prevailing mood is one of grim grotesquerie (“suffused with violence, sexual confusion and perversity” as the blurb on the back cover puts it). There is most assuredly “something nasty in the woodshed”.

I think the decision to use Dorset dialect words and phrases more or less liberally throughout works very well indeed. Their buzz and burr conjures up an intense sense of place that is meanwhile anachronistic and apart from current reality, given that many of those words are (apparently) no longer in current use, being salvaged by Harvey from the pages of William Barnes' 1863 Grammar and Glossary of the Dorset Dialect. Readers not from that part of the world are aided by numerous footnotes and a glossary, and for the fainter-hearted, all of the poems are given in plainer English too. All this apparatus can at times seem like overkill, but an excess of hand-holding is probably better than too little.

It’s a highly idiosyncratic book with no few weaknesses, but overall I found it a bold and a compelling work. An odd surprise for me was that I recognized a couple of the ostensibly obscure dialect words therein having previously heard them via another source. My late wife hailed from Newfoundland, which has a rich dialect of its own. On occasion she’d use the dialect word bivver as an emphatic variant of shiver (i.e. with cold); Harvey uses biver, which is explained in her glossary as “to shake or quiver with cold or fear”. And sometimes when brushing her hair, if it were badly tangled, my wife might complain of it being clitty. Harvey uses clitty a few times, glossing it as “stringy and sticky, tangled in clods or lumps”. Perhaps it’s no coincidence then that a relative of my wife’s, on tracing their shared ancestry, found a number of forebears who’d moved to St. John’s from the Poole area of southeastern Dorset.